Sometimes you are asked to go on a journey because you are expected to fail. You could always refuse to going on that journey; some people will say you made the right decision, others will be upset, because you were suppose to failure. Maybe because they don't like you, maybe because they are jealous of you professionally, or maybe they just wanted to kill a new idea, and you had a enough creditability that if you failed the new idea died with your failure.

Or maybe just maybe, you get to see the possibilities, that the journey has to offer, maybe you understand that even if you fail you would have grown for taking the journey. Plus you would have no idea whatsoever which ways the journey will take, because you would be traveling on a path never taken before. If you decide to take the journey you will come to forks in the roads where almost every sign, every piece of advice you get whether you seek it from "experts" or is given unsolicited by "experts" will tell you it just isn't possible, you doing it wrong because it have never been done that way, you are taking unnecessary or stupid risks, or you gave it a real good try, they is nothing to be ashamed of.

In the end maybe the most important thing you will learn from your journey is that you know far more, and are far capable of doing more than you every believed possible. Maybe the second most important thing you would have learned on your journey is which of your many good time friends that you can really trust. The third most important things is if you are trying your best, making the effort, the "real experts will seek you out and give the encouragement and honest advice and support you need to succeed.

The best are only willing to help the people who are willing to help themselves. As in the "Field of Dreams" if you build they will come, if you take the trip the teachers will find you.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

_small.jpg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

_small.jpg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

|

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

_small.jpg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I was told that I was being assigned to a special project called EAF 2000. It was an experimental project to change the way the Marine built airfields in a combat zone. I asked why I was being assigned to the project if I had very little time left in the Marine Corps. I was told that I had enough time to get the project done. I told them that the only way that I would do the project was if I was given the ability to examine the site by myself. The Wing EAF officer told the Group CO that his office would funds the TAD. I told him that I would need 4 Marines to survey and graph out the project site and he said ok.

When I got out to the project site I knew something was very serious wrong. I went over the drawings at least 3-4 times before I asked for the person that had drawn up the project plans. He told me that he hadnít really survey the site he just eye-balled it. When we surveyed the site it became very clear that as drawn we would have to relocate drainage, we would get to close to the water lines and would have to relocate a road. Not only would this require more personal and equipment it would have seriously delayed the project because it would now have to have environmental impact studies.

I sent the surveyors and draftsmen home and locked myself in my room with my footlocker of engineering books and manuals. After about five days I had drawn up three separate plans each with its own time schedule, personal and equipment requirements and daily work schedules. I returned back to El Toro and told the Wing EAF officer that I was ready to brief. Everyone from the first meeting was there. I told them that the plans that they had provided me just wasnít workable and I gave the reasons why. The Group CO thanked me for my time and effort and got up to leave, but he quickly stop and gave me an angry look when I stated that the concept was workable and that I had three proposals to make it work. When I finished the three proposals the Wing EAF told everyone that he was very confidence that the Commanding General would buy off on my proposals.

I was a fool I didnít realize that I was being used by all sides in this matter. The EAF officer (who liked the work I had done on Mountain Warfare Center Project and the CG who was a fix wing jet pilot wanted the project undertaken. The Group CO and the Asst Wing Commander (a harrier pilot) didnít want the project done. I was a twice past over Captain with less than six months left in the Marine Corps and I was caught in the middle of one of the largest peace-time engineer projects in recent history. If everything went perfectly I wouldnít get any credit as I would be gone. If anything went wrong I would be the fall guy the failure, the failed project was just prove that the Marine Corps was correct in not promoting me to Major.

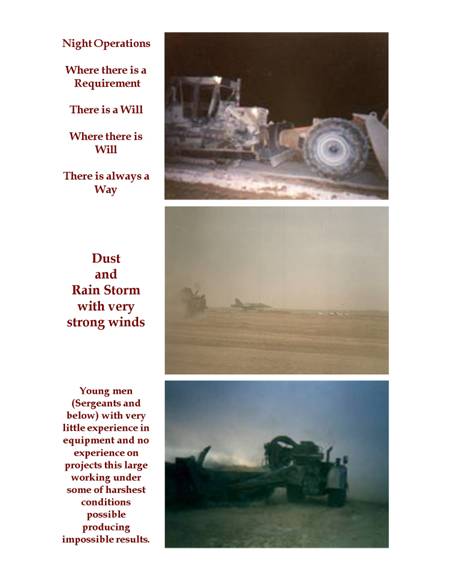

So I was at the crossroads again what would I do. I was beaten and tired from seven weeks living and working long hours in the desert, I had just finish planning for a very large engineer project a project was require cut exceed 20 feet in depth and removing over 300,000 cubic yards of soil while working in temperatures regularly exceeding 115 degrees.

I decided that I would do the best job possible and let the cards fall where they may. I would leave the Marine Corps knowing I had done the best job possible, that I had met or exceeded my own high standards. Little did I know how hard that would be.

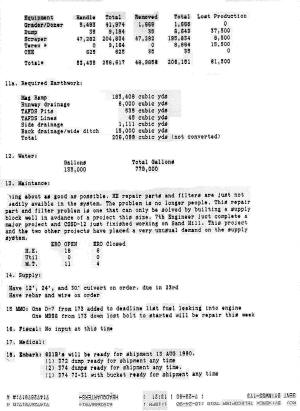

I was not provided with the right types and amount of equipment needed most of the equipment needed repairs. I was not provided with a single engineer officer. I was given four sergeants and the only SNCO was a GySgt that had no engineer background and no one wanted. I was given less than 45 people. I had little to no control of the people as their commands were allowed to send them to the rifle-range and on leave. In comparison an earlier airfield project scheduled for six months at the same site had 204 enlisted Marines, 57 pieces of engineer equipment, along with 29 pieces of motor transportation equipment months and 200 plus Marines to complete their project. The soil stabilization part of the project would have had 135 Marines Sergeants and below alone. Furthermore that project was assigned 11 officers to include 7 combat engineer officers, 1 engineer equipment officer and 1 motor transportation officer.

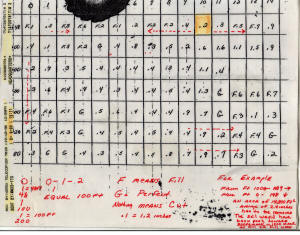

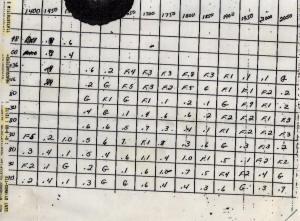

Since failure is never an option we developed a work schedule to get around all our shortages. The first team worked from 6 AM to 2 PM. Monday through Saturday. The Maintenance crew worked on the equipment as needed and had from 2 PM to 4 PM to get the equipment for the night shift which worked from 4 PM to 10 PM Monday to Friday. Each work crew work flip work schedules each week. I went to other engineer units on base and asked if they wanted to give their operators training, and in some cases I told them if they were willing I would pay for the fuel and repairs out of my budget if they were willing to provide operators and equipment. When the reserve units came in during the summer I offered them the same deal. There was no way engineers would turn down the opportunity to operate earth-movers, dozers, compactors and graders. I then had all the operators do a weekly inspection on their equipment every day and do a monthly on their equipment each week which resulted in very low down time.

Using this schedule we were able to get way ahead of schedule. On one occasion a Captain and some senior SNCOís came out to the project site and started chewing out my people for how they were dress and how they were talking and acting on the job site. It was often over 120 degrees in the equipment cabin so I was loose with the dress code. I didnít require any saluting on the job site, and I had the surveyors take hourly reading and had the draftsman post a new cut and fill chart every four hours. Any operator had the ability to call everything a sudden stop if something seemed out of place. The SNCOís did not feel that I had a professional work site. Not one of these people had spent a single day out at the project, not one had gotten inside the cab of a piece of equipment. They even drove up in an air-condition car. So I told them if they had any problems with my people they had to talk to me, not to my people. The rule was simple they were not to take any directions concerning the project whatsoever from anyone except me. Needless to say they were very upset.

They went back to the rear and told everyone that the project was in total disarray and would never be finish on time let alone right. This resulted in a visit by the squadron CO, the SgtMajor, The Operations Officer and a few others. I talked to them all, I told them what was going on and what the plans were calling for and I exampled to the CO what on any engineer project we do what we can when we can in order to save time and resources in the end. He was happy with what he saw. However, now the group wanted control over my budget. They started denying my request for equipment such as laser equipment for final grade, new cutting blades for the earth-movers. I had to go to the Wing EAF officer because it was the Wingís money.

I was pissed because the Group was trying to use my cost center and my funds to order repair parts for broken equipment back in the rear. On a number of occasions the Group HQ tried to ship me equipment that was broken which I had inspected and refused. I had told everyone about the fixed readiness reports and now it was coming back to bit the Group in the ass and it was its own project that was being affected. I refused to cover for the Group. So the Group started pulling people back, and the project started losing work output. As the end of July was rolling around the job was almost on schedule, we had lost that much time.

I was also at the end of my rope after seven weeks in the desert, planning for the project and now almost 3 months of being the only officer working from 5 AM to 11-12PM five days a week, and 5 AM to 4 PM on Saturday and much of Sunday, planning the next weekís schedule. This combined with the fact that I was not allowed to say on base during this period having to live in a number of different motels out in town. I was toasted. I had very little left in the tank. I didnít know how much longer I could go on.

I didnít know what was wearing down the worse was it that as soon as this operation was over I would still be thrown out of the Marine Corps or was it when it became critical I was the engineer that everyone wanted. Four months earlier I was just a passed-over failure than no one wanted to be around. I had a very difficult time with the fact that many of the other engineers in the unit were living in air-condition buildings and had showers every day when I often found myself hour after hour in the hot sun. I knew I was being used. Each day it got worst and worst. My left shoulder and arm was almost of little use, the doctor at 29 Palms had put me on pain killers, but now in an attempt to rest it my right arm was going dead. I injured my right knee in the loose sand and would have surgery on it later.